The road to the euro

Nowadays, the euro is part of our daily life, but the story behind the creation of this single currency goes back a long way and involved multiple stages.

In short

Since 1 January 2002, we have been making our payments in euros in Belgium and in a number of other countries. However, there have been previous examples of single currencies and monetary unions.

It was in the Low Countries that the first attempt at monetary unification took shape in 1434, when Philip the Good put a common currency into circulation in Flanders, Hainaut, Holland and Brabant. Then, in 1865, our country was once again part of a monetary union, when Belgium joined the Latin Monetary Union.

The Bretton Woods agreements, which led to the establishment of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1944, paved the way for economic recovery after the war and eventually led to the signing of the Treaty of Rome in 1957 establishing the European Economic Community. The objective was to form a Common Market.

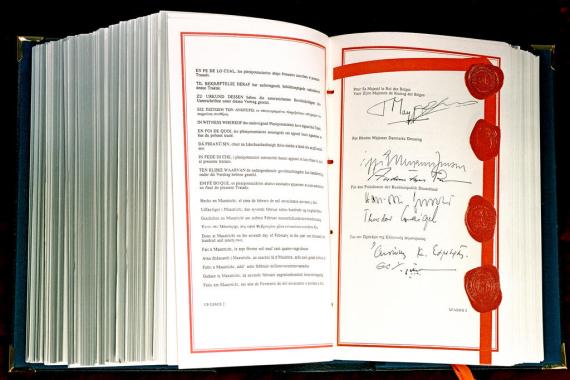

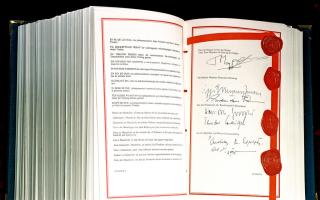

The project to set up an Economic and Monetary Union slowly but surely took shape over the following decades, with the creation of the European Monetary System (EMS) in 1979 and the signature of the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992, which laid a new building block towards setting up a common currency. The euro was introduced in a cashless form in 1999, while the coins and banknotes were put into circulation from January 2002.

There have been several examples of common currencies and monetary unions in the past, before the introduction of the euro. In the Low Countries, it was not until the rule of the Dukes of Burgundy that there was any genuine monetary unification. For instance, in 1434, Philip the Good created a common gold (cavalier) and silver (vierlander) currency for all his northern counties and duchies (Flanders, Hainaut, Holland and Brabant).

Then, in 1865, upon France’s initiative, the Latin Monetary Union was born. The Union set the exact weight of the gold coins and silver sub-divisions of the five member countries: Belgium, France, Italy, Switzerland and Greece (from 1868). Thus, under various names (franc, lira, drachma), a monetary unit existed as a precursor to the euro.

At the end of the Second World War, a new international financial order was established by the Bretton Woods agreements (1944). The dollar was convertible to gold at a fixed rate, while the other countries taking part in the new system undertook to their exchange rate fluctuations within a band of 1 per cent against the dollar. Thanks to these agreements, two new organisations appeared: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB).

In 1957, six countries including Belgium concluded the Treaty of Rome establishing the European Economic Community (EEC). The EEC’s objective was to set up a Common Market enabling the free movement of people, goods, services and capital. The signing took place under the initiative of a few major pioneers of European thought, such as the Belgian Foreign Minister, Paul-Henri Spaak, the former President of the European Coal and Steel Community, Frenchman Jean Monnet, and the Secretary of State in the German Foreign Ministry, Walter Hallstein.

The project to set up an Economic and Monetary Union slowly but surely took shape over the following decades. In 1970, the Werner Report expected it to be established within ten years, but the project took longer than planned. A major obstacle emerged in 1971 when President Nixon suspended the gold convertibility of the dollar, calling the Bretton Woods system into question. This caused great instability on the foreign exchange markets, casting serious doubt on the parities between European currencies. A structure that could potentially lead to monetary union was then put in place to guarantee a minimum degree of stability, at least at the European level. In 1972, the “snake in the tunnel” was set up under the Basel Agreement. The idea was to reduce the margins for the fluctuation between European currencies to 2.25 per cent on either side of their parity with the dollar. In 1973, the dollar exchange rate stopped being fixed and a system of floating exchange rates came into force. In Europe, Germany, France, the Benelux countries and Denmark decided to keep the fluctuation bands for their currencies against one another. Norvway and Sweden then joined the system through bilateral agreements. A core element of stability had therefore lasted within the generalised system of floating exchange rates. If need be, provision was made for the participating countries’ central banks had to intervene. But the oil shocks, the divergent economic policies conducted by member countries and the instability of the foreign exchange markets stopped the success of the currency snake in its tracks. Most of its members pulled out of it in less than two years, reducing it to a Deutsche Mark zone.

In 1978, the proposals put forward at the Bremen Conference marked the return to European monetary cooperation. The European Monetary System (EMS) was then launched in 1979. It had three constituent parts: the creation of the ECU as a monetary unit, exchange rate stability between the currencies (thanks to central bank interventions) and solidarity between member countries through the provision of credit facilities. The system’s unit of account was the ECU (European Currency Unit): a basket of European currencies whose value was equal to the average of those of its constituent currencies.

While several countries decided to actually issue ECUs, Belgium was the only one to make them legal tender. Between 1987 and 1998, Belgium minted silver coins of 5 ECU and 50 ECU gold coins. So, in a sense, our country was the first to issue a common European currency.

In 1988, the Delors Committee was given the task of proposing specific proposals for progressing towards Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). The Delors Report outlined three stages, the last of which was to set up a single currency, paving the way for the European Union. the Treaty of Maastricht, amending and supplementing the Treaty of Rome, outlined the timetable for the introduction of this currency. It was signed in 1992 and entered into force the next year.

In December 1995, at the Madrid Summit, the heads of State and Government decided to christen the single currency the “euro”. This name had been put forward by Germain Pirlot, a Belgian teacher of Esperanto, in a letter dated 4 August 1995 addressed to Jacques Santer, the then President of the European Commission, who apparently backed this idea.

The transition scenario featured two key dates: on 1 January 1999, the euro was officially launched, but could only be used for cashless payments (cheques, bank transfers, bank cards, etc.). Euro notes and coins were put into circulation on 1 January 2002. During this transitional period, the participating countries’ economic systems continued to function on the basis of national monetary units. They were non-decimal sub-divisions of the euro.

Twelve countries paid with the common currency, the euro, for the first time on New Year's Day in 2002. With the addition of Croatia, the number officially stands at 20 countries in 2023. The microstates of Monaco, San Marino, Andorra and Vatican City also use the euro, thanks to an agreement they reached with the European Union. Montenegro and Kosovo also use the single currency, but without a formal agreement.

Bibliography

- ABRAHAM J.-P. et C. LEMINEUR-TOUMSON (1981), « Les choix monétaires européens 1950-1980 », Cahiers de la faculté des Sciences économiques et sociales de Namur, Namur, série Documents et points de vue, n° 4, avril.

- BARTHALON O., I. BIBAC et C. ERNST (2009), « L’euro, une devise stable devenue monnaie de réserve », Banque et stratégie, Paris, n° 274, octobre, 23¬–32.

- CUKIERMAN H. (dir.) (1997), « De l’écu à l’euro, le traité de Maëstricht et son application », Intérêts, Paris, Groupe CPR, n° 12, 1er semestre.

- DE STRYCKER C. (1978), « Le franc belge dans le serpent monétaire européen », Centre d’études financières. Collection des études et conférences, Bruxelles, n° 285, février, 3–17.

- FLOC’HLAY J.-M. (1996), La monnaie unique. Pourquoi? Quand? Comment?, Lagny-sur-marne, Eudyssée.

- JEAN A. (1990), L’écu, le SME et les marchés financiers, Paris, D’Organisation.

- LOUIS J.-V. (2009), L’Union européenne et sa monnaie, Bruxelles, Université de Bruxelles.

- TERRAY J. (1999), Le passage à la monnaie unique, Paris, Dalloz.

- TUROT P. (1976), Le “serpent” monétaire: histoire, mécanismes et avenirs, Paris, De l’Épargne, Collection De quoi s’agit-il?.

- Arrêté royal relatif à la démonétisation des pièces de monnaie libellées en Écu, Moniteur belge du 01/12/1998, 38422-38423.

- Germain Pirlot “Uitvinder” van de euro, De Zeewacht, 16/02/2007, 18.

- Musée de la Banque nationale de Belgique (2006), Histoires d’argent, 32.

- « Rome…d’hier à demain » (2007), Connect, Revue du personnel, n° 2, mars, 6–7.