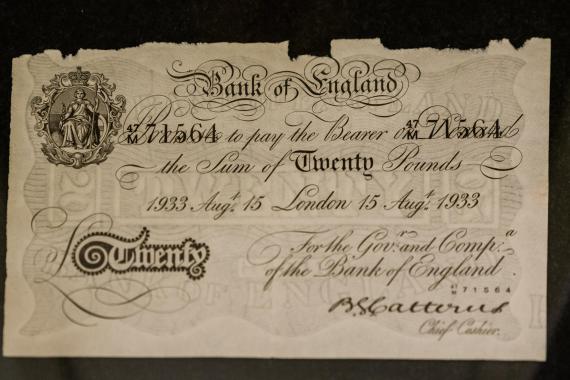

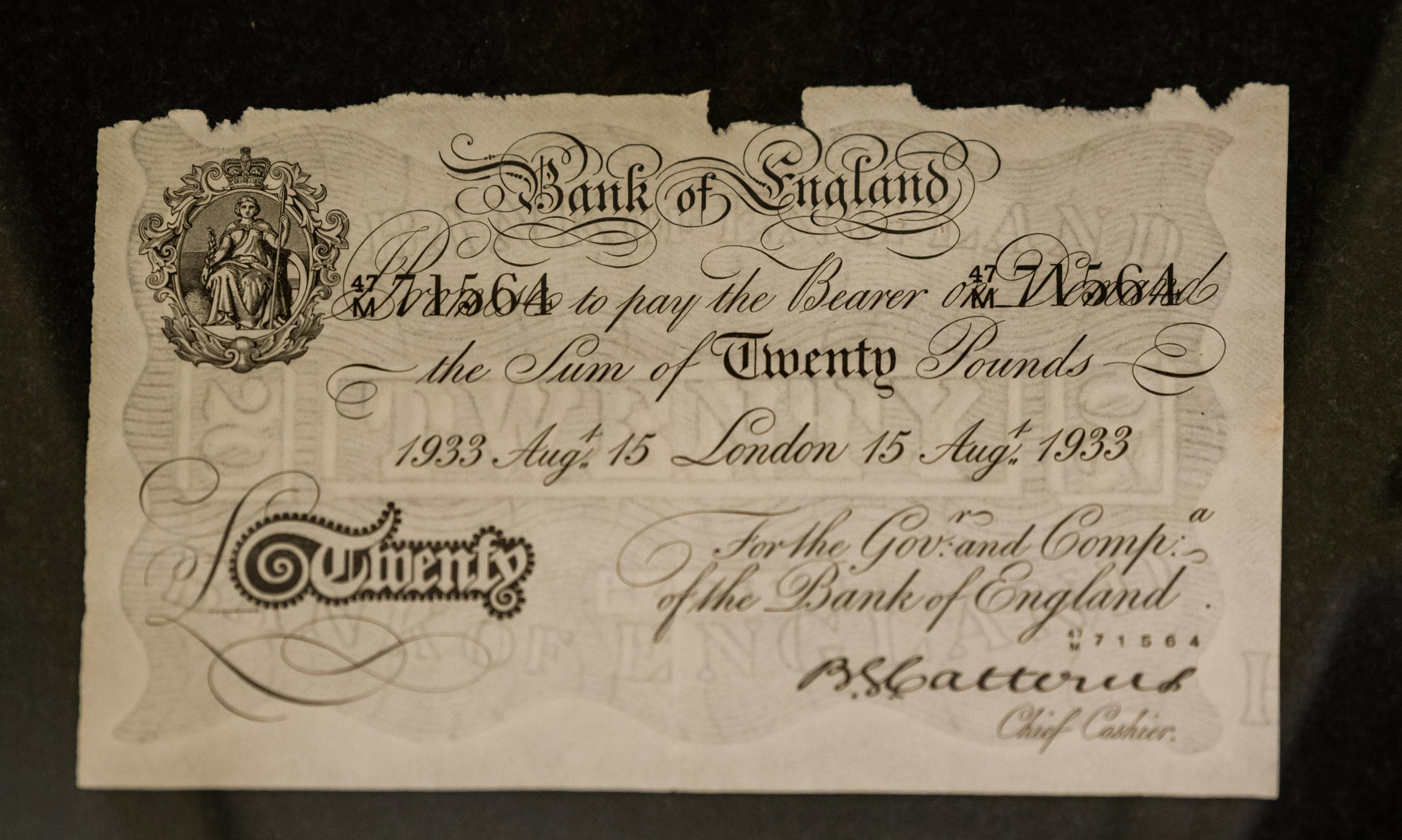

A forged banknote at the National Bank of Belgium!?!

In World War II, the Nazis produced counterfeit sterling banknotes in order to destabilise the British economy. One example is kept in the museum.

In short

This 20-pound-Sterling banknote is the only forged note in our Museum. Everything suggests that it comes from the United Kingdom. But not at all! In early 1940, the Nazis decided to attack the British economy and wanted flood the country with counterfeit banknotes in a bid to trigger hyperinflation. They then launched a vast counterfeiting operation by creating forged banknotes of such good quality that even the Bank of England could not always detect them. For months and months, the British notes were analysed from all sides to try to detect the production secrets. From July 1942 onwards, the Nazis hoped to use these forged banknotes to finance German intelligence operations. For security, the Berlin workshops set up in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. The presses turned until the evacuation of the camp in 1945. The Nazis were careful to throw away all trace of their wrongdoing (printing plates and notes) in a lake. For many years, the forged banknotes circulated on the black market, forcing the Bank of England to put a new series of banknotes in place.

This item is the only false note in the Museum's showcases. You are probably wondering what is the point of exhibiting a forged banknote, and to understand why, we need to delve into the context of the Second World War. This banknote is actually just one of the elements of one of the biggest forgery operations of all time, one staged by Nazi Germany.

Operations Andreas and Bernhard

"Unternehmen Bernhard" and its predecessor "Unternehmen Andreas" were the names of two secret Nazi projects meant to destabilise the British economy during the Second World War. It was one of Hitler’s collaborators, Reinhard Heydrich, who set out the plan to him as early as 1939. The original idea was to flood the United Kingdom in various ways, such as dropping masses of false Bank of England notes to discredit the British currency by triggering hyperinflation that would destabilise the British economy.

Germany knew perfectly well what unlimited inflation could mean to the economy, as it had gone through the same situation just after the First World War. Hitler immediately accepted.

He was certainly not the first political leader to launch a money counterfeiting operation. Napoleon had already done so. And, during the French Revolution, England had also produced false assignats and flooded France with them. So, there was a lot there in the past to inspire Hitler and his collaborators.

The Nazis set to work. One of the first difficulties was the production of paper absolutely identical to that produced by the Portal paper mill, the Bank of England’s supplier. Real British banknotes were thus sent to various laboratories and universities for scientific analysis. They discovered that the British pulp was made from pure linen and that it was used, soiled and laundered and that this paper could only be handmade. The Nazis managed to reproduce almost identical paper to that used in real banknotes.

The two successive counterfeiting teams set out to solve the problems of detecting all the security features. The original banknotes had been photographed and clichés enlarged to facilitate tracking of details. This enabled some minor defects to discovered, initially assumed to be printing flaws, but found over different banknotes and were actually security features. In this way, the engravers learned that there were at least 150 of them. Consequently, the technicians duly copied all these 'errors' and thus obtained counterfeits bearing all the security features. As an example, they discovered that the small spot in the middle of the "i" in the word Five was in all the £5 notes.

After these operations, the banknotes had to be aged before they could be put into circulation. Now, the only way to age a banknote prematurely was to reproduce exactly what happens to them in real life. The ups and downs in the life of a banknote and the habits of its successive owners were classified and reproduced in chain. For instance, some employees were specialised in folding, while others were instructed with rubbing and other stamped the back of some banknotes as did bank branches in the United Kingdom sometimes. Everyone had to carry out these different operations with dirty hands. Moreover, some notes went through extra ageing that involved small tears and other paper pull-outs.

While the end result satisfied the workers and technicians, it was still worth knowing whether a banker could also be fooled. In 1941, the Nazis asked one of their agents to produce a large stack of the counterfeit notes to specialists in their bank (which happened to be Swiss), together with a letter, supposedly from the Reichsbank, asking the Swiss bank to determine whether these "doubtful British notes" were actually genuine. The bank acknowledged the authenticity of the banknotes. But the Nazis still demanded a second opinion from the Bank of England itself. Three days later, after a thorough examination using the most perfected methods, the reply was, to their great surprise, identical! 90% of the counterfeit notes had passed the test.

Despite this success, the Nazis were not able to avoid one major risk. They had not been able to break the numbering system on British banknotes. They also ran the risk that notes bearing identical numbers would turn up in the same bank and thus raise suspicion.

A counterfeiting workshop in a concentration camp

Unternehmen Andreas had its headquarters in Charlottenburg, just west of Berlin in an old training centre for the Nazi security service. Bernhard Krüger, a civil engineer and an SS major who was involved in forging documents, took over in 1942 and gave his first name to the subsequent operation. He formed a new team of Jewish prisoners comprising financial experts, engravers, graphic artists and expert printers. For security reasons, the whole team moved behind closed doors to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp just north of Berlin, in August 1942. The plan was of course for the “employees” to be disposed of afterwards. The liberation of the camp by the American Army in April 1945 only managed to save 30 of the 130 prisoners.

While the goal of the operation had previously been to throw the British economy off balance, Heydrich had another target: creating almost unlimited financial means for his intelligence service. So the idea was to exchange these forged banknotes for various currencies to provide for the German foreign intelligence services.

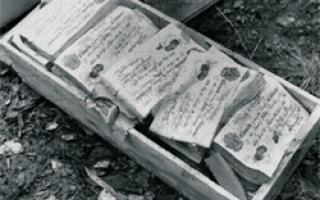

When the Nazis were defeated, printing works material and stocks of remaining banknotes were dumped by the SS – misinterpreting an order – into the Toplitzsee, a lake in between Innsbruck and Salzburg so as to wipe out any trace of their wrongdoing. Patrols were instructed to recover them, but it is estimated that hundreds of thousands of pounds sterling were not found. They reappeared on various black markets in Europe over the subsequent years, and it is likely that a lot of them were accepted by the Bank of England.

What was the UK reaction?

By December 1939, the British Embassy in Paris had informed the Treasury of the Bank of England that the German Government intended to copy the British pound. The first forgeries turned up in September 1942. In 1943, the Chancellor of the Exchequer (Minister of Finance) announced that the Bank of England would no longer issue notes of ten pounds and above. In this way, notes circulating abroad could better be isolated. The security features of the five-pound note were tightened up by inserting a metal thread in it. But it was not until 1957 that a new colour five-pound note appeared.

Never again has banknote counterfeiting reached such perfection, absolutely undetectable according to the experts. In fact, only a few errors with matching numbers and issue dates were able to be noted in the accounts kept by the Bank of England. The Austrian-German film The Counterfeiters (2007) depicts part of these operations.

Video on the same topic

Bibliography

- Bower P., Operation Bernhard: The German Forgery of British Paper Currency in World War II, in Bower P. (ed.). The Exeter Papers, London, The British Association of Paper Historians, pp. 43–65.

- Burke B., Nazi Counterfeiting of British Currency during World War II: Operation Andrew and Operation Bernhard, San Bernardino, California, 1987.

- Byatt D., Promises to Pay. The first three hundred years of Bank of England notes, Spink, London, 1994, p. 45-56.

- Stahl Z., Jewish Ghettos’ and Concentration Camps’ Money (1933-1945), Israel, 1990.