Belgian gold in the hands of foreigners

When World War II broke out, the Belgian State evacuated its gold reserves and entrusted them to France. But the enemy troops advanced rapidly. Belgian gold was at risk.

In short

At the end of the 1930s, the threat of war was growing in Europe. As a precaution, the National Bank evacuated two-thirds of its gold to the United Kingdom, United States and Canada. In early 1940, the Finance Minister Camille Gutt decided to entrust to the remaining third, 200 tonnes of gsold, to France. But the German troops were advancing more rapidly than expected on French territory. The Banque de France then sent the Belgian gold to the port of Lorient so as to send it on to the United States, as agreed with Belgium. The ship finally set anchor in Dakar, a French colony. In the hope of liberating its prisoners of war, France gave the gold to the German Reichsbank, which quickly recovered it. Following a lawsuit launched in New York, France was obliged to repay Belgium in full. It recovered part of its losses as, in 1945, American troops found a stock of gold in a German salt mine, including the Belgian gold stolen in the first place.

During the second half of the 1930s, there was a constant and growing threat of war. Belgium sensed the urgency to transfer most of its stocks of gold and other valuables abroad for safe keeping. A scale model in the Museum shows the A4 ship which was used to transport valuables from several NBB branches to the United Kingdom in May 1940.

Belgium’s gold reserves were also sent abroad for safety. The transport of the stocks of gold went less smoothly than hoped for and part of the stocks were condemned to an odyssey.

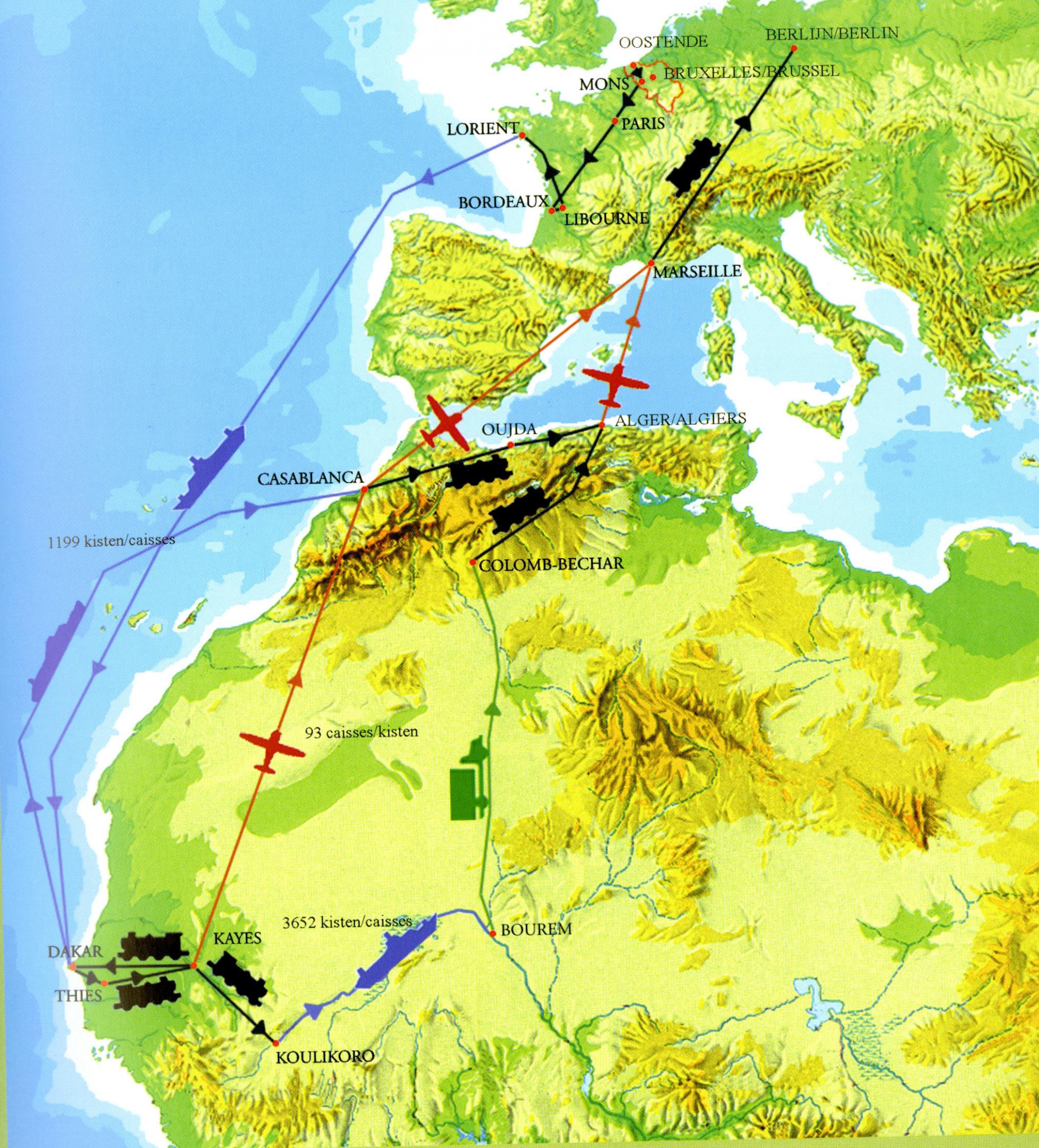

Before the outbreak of the Second World War, Belgium's gold reserves amounted to some 600 tonnes, 200 tonnes of which was sent to the UK and another 200 tonnes to the US and Canada. The remaining 200 tonnes stayed in Belgium to meet the statutory cover requirements in respect of the banknotes. As the international tension increased in late 1939-early 1940, those assets were removed on the orders of the Finance Minister Camille Gutt and entrusted to the Banque de France. 198 tonnes of fine gold were packed into 4,944 chests and transported from the port of Ostend to Bordeaux and Libourne where the gold was guarded in the Banque de France’s vaults. At the time of the German invasion, on 10 May 1940, only a very small amount of gold still remained in the National Bank of Belgium’s vaults.

The German troops advanced more rapidly than expected on French territory. At the beginning of June 1940, the Banque de France informed the French Admiralty of the presence of Belgian gold which urgently needed to be shipped overseas. The Navy took the gold to Lorient, the nearest naval port, where the chests were loaded on to the auxiliary cruiser Victor-Schoelcher. The ship should originally have transported the gold to the US, but it never reached its destination. On 18 June 1940, the ship weighed anchor in the port of Dakar in the French colony of West Africa. The gold was transported 65 km further to the military base of Thiès. However, the area was much too close to the sea and they feared a possible invasion by the enemy. For this reason, the French colonial authorities decided to move the Belgian gold further inland. They sent it to Kayès, in the middle of the Sahara Desert, some 500 km from Dakar.

But the National Bank of Belgium was not really happy with the fact that, against its wishes, France had sent Belgian gold to Kayès and not to the US (as hoped). Hubert Ansiaux, who was running the National Bank's business from London, sent the French central bank a notice of default. This did not really have any immediate effect. On the contrary, at the end of 1940, France and Germany reached an agreement under the Armistice talks. France agreed to give the Belgian gold to the German Reichsbank as an “atoning sacrifice”. Under pressure from the French Prime Minister Pierre Laval, who expected something in return from the Germans, (the release of French prisoners of war), the Banque de France reluctantly agreed to the transfer of the gold, against its better judgment.

The gold was transported from Central Africa to Algeria and from there to Marseille. The Reichsbank then sent the gold by train to Berlin, where it was stored in its vaults. Transporting the gold did not go to plan and could only be completed in May 1942. It was clear that the French were not collaborating faithfully. After the gold was stocked in the Reichsbank’s vaults, the commissioner for the German Four-Year-Plan, Hermann Göring, confiscated it. Following the seizure, all the gold bars were melted down into Prussian Staatsmünze. To remove any suspicion of the gold’s provenance, the Nazis hallmarked it with the dates 1936 and 1937.

Meanwhile, Belgium was not giving up and Georges Theunis, a Regent at the National Bank of Belgium, launched proceedings in New York against the Banque de France, on 5 February 1941, to reclaim part of the French gold. A lengthy legal battle followed and it was not until April 1943 that the main hearing started. However, the court suspended the decision because the war prevented the French from calling any witnesses or submitting any evidence. In April 1945, American troops found a massive store of treasures, in a salt mine near the small Thüringian town of Merkers, the American troops discovered a massive store of treasures: works of art, valuable objects looted by the Nazis, plus a stock of gold, including part of the gold stolen from the National Bank. The Americans also found the Reichsbank's records relating to the gold. This made it possible to check precisely what route had been followed by the largest part of the stolen Belgian gold. The Nazis has primarily used it to obtain hard currency. They could then purchase commodities from Spain, Portugal and Sweden, as well as parts for the weapons industry. All the gold that the allies found in Germany was collected into a pool which was used by the Tripartite Commission for the Restitution of Monetary Gold to meet the claims of the countries whose assets had been plundered. Under pressure from the Allies, neutral countries such as Switzerland also paid precious metal into the gold pool. The National Bank of Belgium also submitted a claim for compensation on behalf of the French central bank. In the end, the Banque de France received around 130 tonnes, and thus recovered two-thirds of the gold which it had lost.

Bibliography

- Buyst E. & Maes I. (e.a.), La Banque nationale de Belgique, du franc belge à l’euro, Bruxelles, Racine, 2005, 141-148.